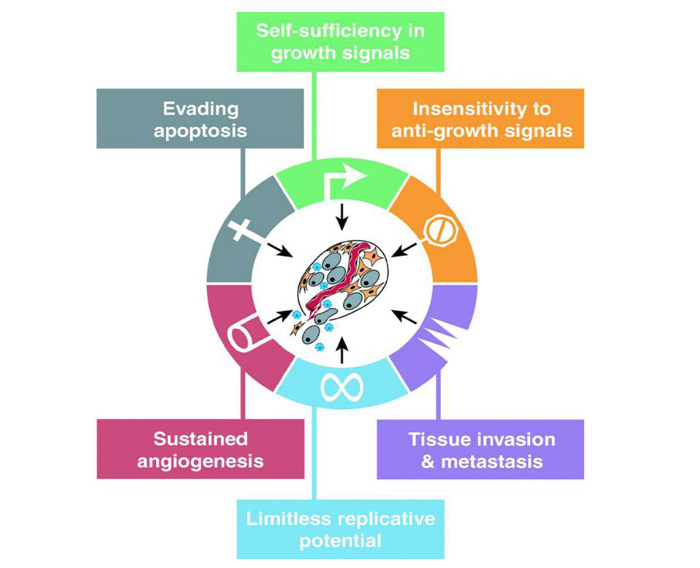

DNA mutations result in defects in the regulatory circuits of a cell, which disrupt normal cell proliferation behaviour. However, the complexity of this disease is not as simple at the cellular and molecular level. Individual cell behaviour is not autonomous, and it usually relies on external signals from surrounding cells in the tissue or microenvironment. There are more than 100 distinct types of cancers and any specific organ can contain tumours of more than one subtype. This provokes several questions. How many of these regulatory circuits need to be broken to transform a normal cell into a cancerous one? Is there a common regulatory circuit that is broken among different types of cancers? Which of these circuits are broken inside a cell and which of these are linked to external signals from neighbouring cells in the tissue? The answer to these questions can be summarised in a heterotypic model, manifested as the six common changes in cell physiology that results in cancer (proposed by Douglas Hanahan and Robert Weinberg in 2000). This model looks at tumours as complex tissues, in which cancer cells recruit and use normal cells in order to enhance their own survival and proliferation. The 6 hallmarks of this currently accepted model can be described using a traffic light analogy

Hallmarks of Cancer

Grading

i) Self-sufficiency in growth signals

ii) Insensitivity to antigrowth signals

iii) Evasion of apoptosis

iv) Limitless replicative potential

v) Sustained angiogenesis

vi) Tissue invasion and metastasis

Copyright ©2018 all rights reserved

Designed by Purpleno.in